Part 1 – Getting rid of the fairy stories – is available here.

Messing around in a bucket

Those somewhat fictitious “traditional” ancestors of ours made wine in anything they could find. Usually, they would have started it in a big bowl covered with a cloth and then finished it off in a salt-glaze earthenware pot – at which point they couldn’t see it any longer. And that’s the point at which things can begin to go wrong. A glass or plastic demijohn solves that problem right away, but I’m trying to prove to you that such things are not necessary for such a simple activity as fermenting a solution of sugar. So, get yourself a plastic bucket (you’re going to need one anyway, even if you climb to the dizzy heights of demijohn ownership). It needs to be a food-grade bucket and, ideally, it will have a lid. But even the lid isn’t necessary, as you can cover the bucket quite easily with a tea towel or a bit of wood. Having got your bucket, it needs to be cleaned. Once again, let’s keep to the simplest method. Wash it with hot soapy water and then rinse it. Now, if you poured a gallon of water into the bucket and then took out a glassful, would you be prepared to drink it? If not, why not? – you’ve just cleaned the bucket using the method you use to clean the crockery you eat your food from. However, let’s make doubly sure. Boil a kettle of water and use it to scald all of the interior surfaces of the bucket. There – now it’s sterile.So, what to put in the bucket? I think we may as well attempt to find something which uses as many of the “expert” attitudes as possible (so that none of them can complain!!!) whilst still keeping the simple method I’m insisting upon, but bearing in mind that we need to make a mess in such a manner as to keep the yeast happy and still end up with something drinkable. Right, then – a simple but traditional recipe which will go some way to satisfying the purists, the chemists and the modernists.One of the main put-offs for beginners is the totally stain-making and highly-demanding preparation of the raw materials. Peeling and coring apples for hours on end while at the same time preventing them from browning is a pain in the bum. Strigging and crushing ten kilograms of elderberies is enough to try the patience of a saint. Picking and cleaning gallons of flower-heads means you’re going to miss Match of the Day or Corrie. On the other hand, traditional flower and leaf wines are a sight less messy than any other.

Those somewhat fictitious “traditional” ancestors of ours made wine in anything they could find. Usually, they would have started it in a big bowl covered with a cloth and then finished it off in a salt-glaze earthenware pot – at which point they couldn’t see it any longer. And that’s the point at which things can begin to go wrong. A glass or plastic demijohn solves that problem right away, but I’m trying to prove to you that such things are not necessary for such a simple activity as fermenting a solution of sugar. So, get yourself a plastic bucket (you’re going to need one anyway, even if you climb to the dizzy heights of demijohn ownership). It needs to be a food-grade bucket and, ideally, it will have a lid. But even the lid isn’t necessary, as you can cover the bucket quite easily with a tea towel or a bit of wood. Having got your bucket, it needs to be cleaned. Once again, let’s keep to the simplest method. Wash it with hot soapy water and then rinse it. Now, if you poured a gallon of water into the bucket and then took out a glassful, would you be prepared to drink it? If not, why not? – you’ve just cleaned the bucket using the method you use to clean the crockery you eat your food from. However, let’s make doubly sure. Boil a kettle of water and use it to scald all of the interior surfaces of the bucket. There – now it’s sterile.So, what to put in the bucket? I think we may as well attempt to find something which uses as many of the “expert” attitudes as possible (so that none of them can complain!!!) whilst still keeping the simple method I’m insisting upon, but bearing in mind that we need to make a mess in such a manner as to keep the yeast happy and still end up with something drinkable. Right, then – a simple but traditional recipe which will go some way to satisfying the purists, the chemists and the modernists.One of the main put-offs for beginners is the totally stain-making and highly-demanding preparation of the raw materials. Peeling and coring apples for hours on end while at the same time preventing them from browning is a pain in the bum. Strigging and crushing ten kilograms of elderberies is enough to try the patience of a saint. Picking and cleaning gallons of flower-heads means you’re going to miss Match of the Day or Corrie. On the other hand, traditional flower and leaf wines are a sight less messy than any other.

Aren’t we the lucky ones, then? Someone has gone to all of the trouble of picking flowers for us, and drying them and packing them into easily-handled little containers. What do you think of this as a list of ingredients? … Hibiscus petals (not too traditional, I know, but they are flowers), blackberry and blackcurrant leaves, and rosehips. Not bad at all – all of them ingredients which can be used to make wine all by themselves. These are the ingredients of a typical box of 20 fruit tea bags available from any supermarket for a reasonable price. There’s enough stuff in there to make a gallon of wine and, as it’s sold as a tea, the flavour balance will be at least palatable. It’s a sort of high-tech version of puddling around in your wellies gathering fresh flowers, so we’ve gone some way to satisfy the modernists.

OK, you now have your flavour ingredients. Now you need yeast food, which is quite simply a 1-kilo bag of sugar. Put this on the table next to the box of tea bags. No point in having yeast food, though, without yeast, so get hold of some of that and put it next to the tea bags and sugar. That’s a pretty small and easily manageable pile so far.

Oh – but the yeast. You can go through this whole thing using baker’s yeast if you really, really want to – it will work. It will make wine. But believe me, wine yeast will do the job that much better and, if you use general-purpose wine yeast, it’s dirt cheap. Don’t let’s spoil the ship for a ha’porth of tar, so to speak. Get some wine yeast and, while you’re at it, get some yeast nutrient (which I’ll talk about in a while).

Now, are you sitting comfortably? … … then I’ll begin.

1. Open the sugar bag and tip the contents into the bottom of the bucket.

2. Open the box of tea bags and tip the contents on top of the sugar. While you’re there, squeeze the juice of half a lemon onto the sugar.

3. Boil the kettle and pour a measured two pints of hot water into the bucket.

4. Stir until the sugar has dissolved.

5. Cover the bucket any way you like (so insects can’t get in) and wait for it to cool.

6. Remove the teabags, giving them a squeeze, add six pints of cold or lukewarm water, then sprinkle a level teaspoon of yeast onto the surface of the liquid. Recover the bucket and put it in a Goldilocksy warmish place – not too hot, not too cold (the kitchen should be OK as long as it doesn’t approach freezing).

7. Have a look after 24 hours. There should be some signs of yeast activity – it will appear to have spread somewhat across the surface. Recover the bucket.

8. Have another look after a further 24 hours. There will now be a healthy covering of yeast and a nice yeasty cum winey smell coming from the bucket. Give it all a good stir, recover the bucket and go away.

There you have it – a mess in a bucket without having made too much mess outside the bucket. That mess, over the next week or ten days, is going to turn itself slowly and surely into wine with no more effort on your part. It will all work just as written – but it may not work perfectly.

The problem here is that yeast normally gets part of its food from the solids introduced when preparing fruit for winemaking. Of course, there’s very little solid material in this recipe. The big omission, therefore, is nitrogen – which shouldn’t surprise anyone who’s ever grown a plant. Plants need nitrogen to grow well, and so do fungi – including yeast. But, if you’ve been paying close attention, you’ve already bought some yeast nutrient. So, amend step 6 to read …

6. Remove the teabags, giving them a squeeze, add six pints of cold or lukewarm water and a level teaspoon of yeast nutrient. Stir to dissolve the nutrient then sprinkle a level teaspoon of yeast onto the surface of the liquid. Recover the bucket.

I left this out of the original step because, as I said, it will work without it – but the fermentation may stop before all of the sugar has been used up (and so at a lower concentration of alcohol). Without the nitrogen, the yeast may simply run out of puff. Another reason I left it out is because a lot of people don’t like using yeast nutrient on the grounds that it’s a chemical additive.

They’re correct – it is. My argument, which you are at liberty to accept or reject, is that it’s a chemical additive which, apart from increasing the efficiency of the fermentation, leaves behind only the equivalent of trace elements which are found in garden compost. Let’s take a quick look.

Yeast nutrient, in its most available form, is a chemical called di-ammonium phosphate, a name which is in itself enough to scare anyone away. In case you’re interested, that’s (NH4)2PO4. So, it’s a compound of ammonia (that’s the NH4), and phosphate (PO4). Yeast, having an M.Sc. in chemistry, immediately sets about breaking this up to obtain the nitrogen (that’s the N part of ammonia) and it releases the H part as useless. The H part is, in fact, hydrogen, and will bubble its way right out of the bucket together with the carbon dioxide which the yeast is also busy producing. That leaves the phosphate part which, on being separated from the ammonia, immediately recombines with just about anything else it can find to form a harmless compound, loads of which can be found (and is desirable) in soil, compost, and any garden fertiliser. To my mind, this is not an unfriendly chemical. You must, of course, come to your own decision. Right – that’s the chemists satisfied.

Discussion over – back to the wine. While it has been fermenting away, if you remember from Part 1, it has been producing equal weights of alcohol and carbon dioxide. By the time the sugar is used up, therefore, there will be, theoretically, a half-kilo of alcohol in the gallon of water you added, and a half-kilo of carbon dioxide will have been given off as bubbles. That is an awful lot of gas, and it serves a useful purpose. It’s heavier than air and so sits on top of the developing wine. No bacteria will grow within a carbon dioxide atmosphere, so your wine is protected against infection. It will also kill any insects which might fall in, but that’s shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted – you don’t want them in there in the first place. Hence the covering of the bucket.

But the carbon dioxide does something else. The yeast has multiplied hugely from the level teaspoonful you originally put in there. There are literally millions of yeast cells in a fermenting gallon of wine. And all of them are producing little bubbles of carbon dioxide which rise to the surface, taking the yeast cells with them. Then the bubbles burst and the yeast cells sink until they develop the next bubbles, then up they go again …

The net result is that the lovely clear, red liquid you started with becomes opaque because, try as you might, you simply cannot see through a few million yeast cells. Eventually, though, the sugar runs out and the yeast can no longer produce carbon dioxide. All the cells sink to the bottom and stay there, leaving a clear liquid above them. And that is the signal to you that your fermentation is complete, because you can see all of this happening in the bucket – if you’ve been taking the lid off and having a look once a day or so.

What you have just made is a very light-bodied pale red wine with an alcohol content of about 11% by volume (i.e. just a little over a tenth of the liquid is alcohol). Because it is light-bodied and because there is no appreciable amount of tannin in there and because of loads of other reasons, the wine is as good as it’s ever going to get. There’s no great point in maturing it. It will keep for a year, but there’s no point in waiting that long. It’s a very acceptable wine as long as you’re not expecting a great claret, and will certainly make you giggly if you drink a glass or three.

But it’s still in the bucket and there is a layer of inactive yeast cells at the bottom of that bucket which, if you’re not careful, will swirl upwards and make the wine cloudy again. Now you have the job of getting the wine off the lees (that being the technical term for the residue at the bottom). A sieve will not remove the residue – yeast cells are microscopically small and will go straight through a sieve. You have several choices. You can carefully dip the liquid out using a jug. You can try to gently pour it off. Or you can syphon it off with a plastic tube. Whichever method you choose, you will NEVER be able to recover all of the liquid, so don’t try (if you do get a bit of the residue, don’t worry too much – it’s only yeast and a very good source of vitamin B. Note that for later, by the way – it’s only yeast).

But what are you going to put the wine into? I wouldn’t recommend glass bottles at this stage – that wine may still be fermenting just a little bit and could pressurise the bottles. At this stage, the best thing would be the PET bottles which come wrapped around Coke or lemonade. They can take quite a bit of pressure, you can always release any gas by unscrewing the cap slightly, and the wine isn’t going to stay in there very long anyway.

Et voila – wine. Now you have to taste it. You may think it too dry. There’s a way around that. You may think it far too weedy in body. There’s a way around that. You may think it low in alcohol – there are several ways around that. You may think the flavour too thin and un-wine-like. There are ways around that, too.

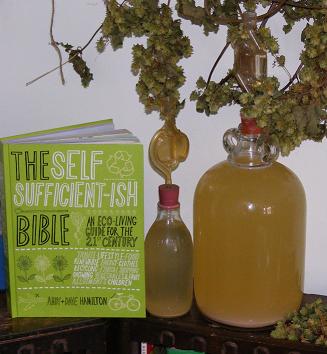

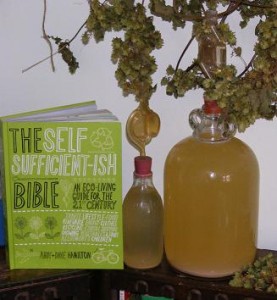

So, that’s Part 3 – how to cheat at winemaking. Plus, probably in Part 4, some ways to make the whole process easier still. So, start looking for a demijohn or two – but don’t lose sight of the fact that you’ve just made wine with no special equipment apart from that bucket.

You really do have a way with words…and wine, don’t you?!

Easy reading, full of no nonsense information set out in a manner which will not scare off the “newbies” amongst us.

No pressure but…when are you posting Parts 3 & 4? 😉

Hi NC – Part 3 is already up in the Author-ish section of the forum, and Part 4 will be joining it soon. It’s Andy’s decision as to when they get posted on this page.

Mike

This sort of simple to follow advice may just see me going out and buying a large food grade bucket (with lid), some yeast and nutrients and giving it a go.

Using herbal teabags? What a brilliant idea! I would never have thought of that! I might be off out to buy a bucket soon too…. : )

Great series – can’t wait for parts 3 and 4. Very true comment about the nature of this wine – no point in “aging” it, best is to drink it young. The other benefit with young wines are all the additional recipes you can now try without running out to buy a bottle of wine.

Well, my fruits of the forest tea wine is brewing away in the kitchen cupboard. I’m hoping the kitchen is warm enough. All i really need to do now is not get impatient and play with it until its done!

Great article! Could you suggest a good website to order general purpose wine yeast and yeast nutrient from? Thanks x

Hi Jinwin

Actually, I can’t – simply because I use a local homebrew shop. But any of the ones you’ll find on the net will be OK. Make sure you compare prices, though – general purpose yeast is all virtually the same stuff, so you shouldn’t be paying over the odds for it.

Mike

Another fab article – thanks so much. I have been making wine for years and now I understand why it works!

It seems so easy. I love the idea of making my own wine, and wouldn’t be too fussy or hard on myself with the results, but I thought the science was beyond me. I’ll try the bucket method. Keen on seeing parts 3 & 4 too in due course.

What great advice! I have wondered about wine making for ages and have always been put off by the complicated recipes around and the variations in them. I like the immediacy of this one too…I don’t have to wait for a year to see if I have done an ok job!

One quick question – if I want to keep some of the wine for a little longer (you said it could keep up to a year)does it need to be in sterilised bottles kept in a fridge, or will it be ok just kept in bottles in the kitchen somewhere?

Many thanks

Sally

Hi Sally

Yes, sterilise the bottles, but they don’t need to be kept in the fridge. Treat it just as you would any other wine.

Mike

Great article, really enjoyed reading it and I am looking forward to following your instruction and making my own wine..Thank you!

hi i have tried this tonight,i hope its drinkable! has anyone any sucess stories? thanks.